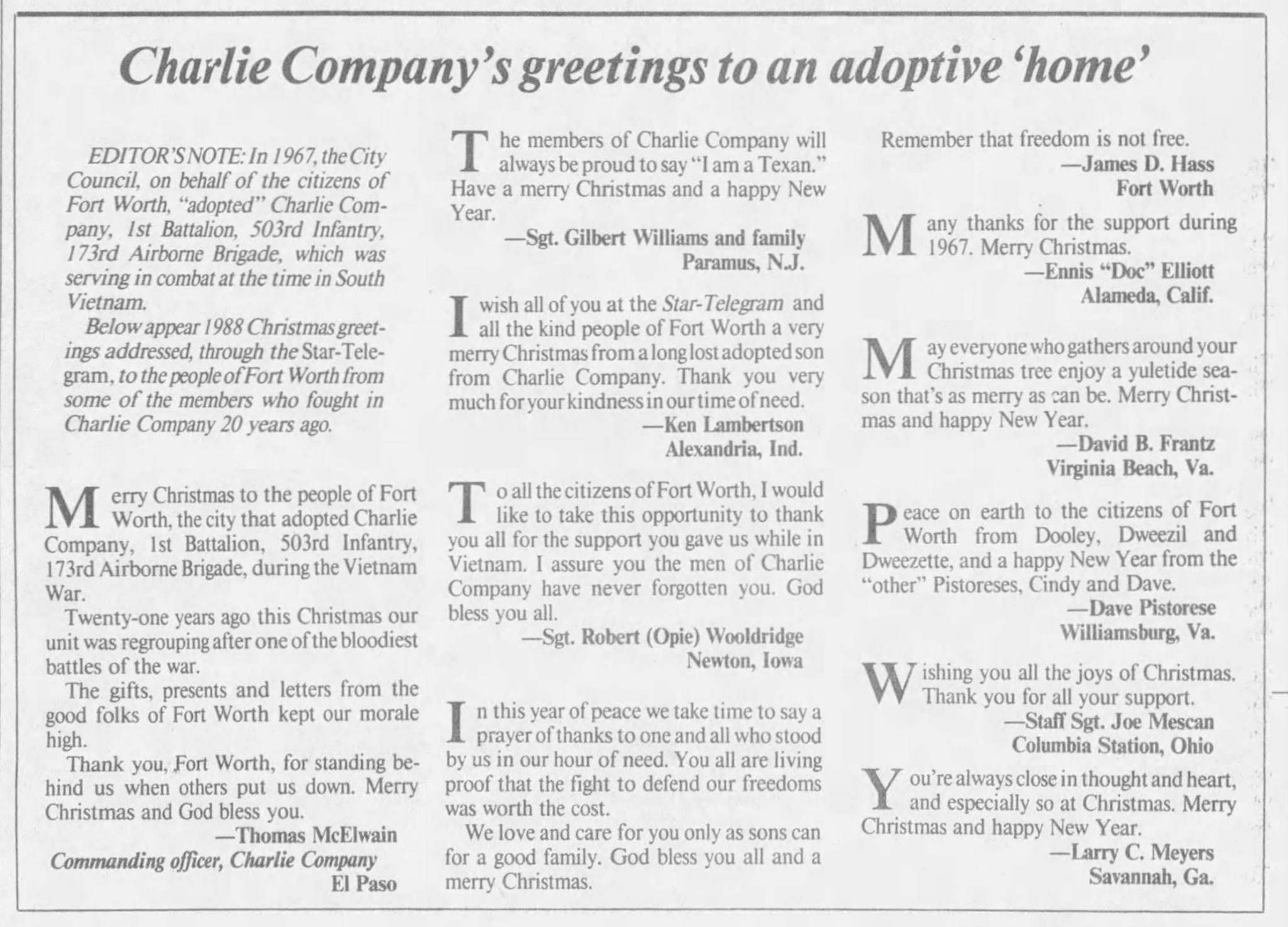

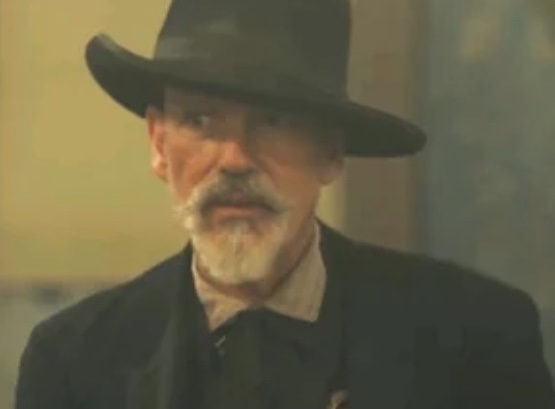

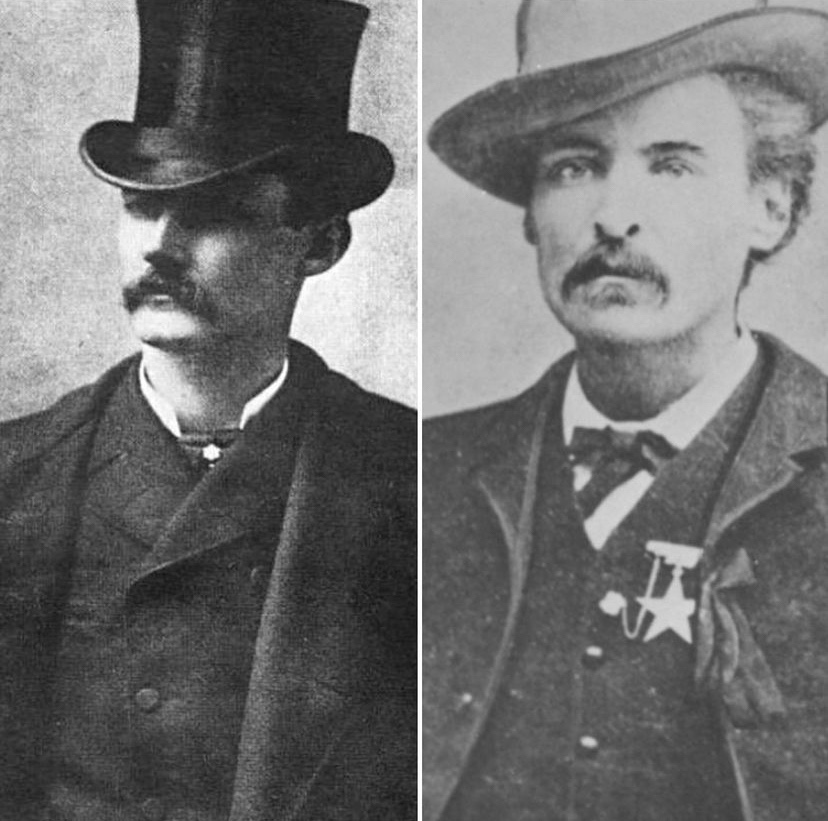

So much excitement in Fort Worth since the filming of Paramount’s “1883” a prequel series to “Yellowstone” the ancestors of the Duttons. If you’re like us, you are thrilled to see any snippet of Fort Worth Stockyards cross your screen. In “1883,” Billy Bob Thornton plays Marshal Jim Courtright, a very real gunman from American history…from Fort Worth history! Born Timothy Isaiah Courtwright, the Illinois native after serving in the Civil War, went on to become the marshal in Fort Worth. Know for his long locks he carried the nickname Longhaired Jim.

You may have heard the story of bad blood between Luke Short and Longhaired Jim that ended in a shootout. No?! Well, here goes!

The two men met on the evening of Feb. 8, 1887 at about 8pm and a challenge was issued by Courtright. Luke Short was called out of the White Elephant Saloon on Fort Worth’s downtown Main Street. They stood facing each other just a few feet apart. Short assured Courtright he had no gun and moved to show him by lifting his vest. It was dark, Courtright had been drinking and he mistook it as a go for his gun. Courtright yelled, “Don’t you pull a gun on me.” Courtright went for one of his two 45’s on his hips. Courtright outdrew Short, in the process his 45’s hammer caught on his watch chain. Luke drew his pistol and got off the first shot. Short then fired four more shots and Courtright fell to the ground on his back dying in bloodshed.

Luke Short was released from prison after a short examination trial with $2,000. bond, it was a clear case of self-defense with the only witness noting Courtright pulled his trigger first. Short ended up paying for Courtright’s funeral, $20. His funeral procession was one of the largest Fort Worth had ever seen.

We are hoping to see “1883” at the White Elephant Saloon portray this event…we’ll see!